Pentagon budgets today can make eyes water, yet they pale compared to Imperial Japan’s 1930s gamble on the Yamato—a 72,000-ton floating fortress that embodied the military-industrial complex run amok. This steel behemoth wasn’t just a warship; it was Japan’s Hail Mary pass in naval strategy, their concrete manifestation of the Kantai Kessen doctrine that naval officers clung to with religious fervor. The same institutional thinking that gave us the Maginot Line gave Japan the Yamato. Military bureaucracies rarely innovate; they perfect yesterday’s weapons for tomorrow’s wars. The Yamato’s tragic story reveals what happens when deeply entrenched admiralties refuse to acknowledge technological disruption—the naval equivalent of Blockbuster dismissing Netflix. Japan bet the imperial treasury on battleship supremacy just as aircraft carriers rendered them obsolete.

Disclaimer: Some images used for commentary and educational purposes under fair use. All rights remain with their respective owners.

Yamato’s Construction and Design

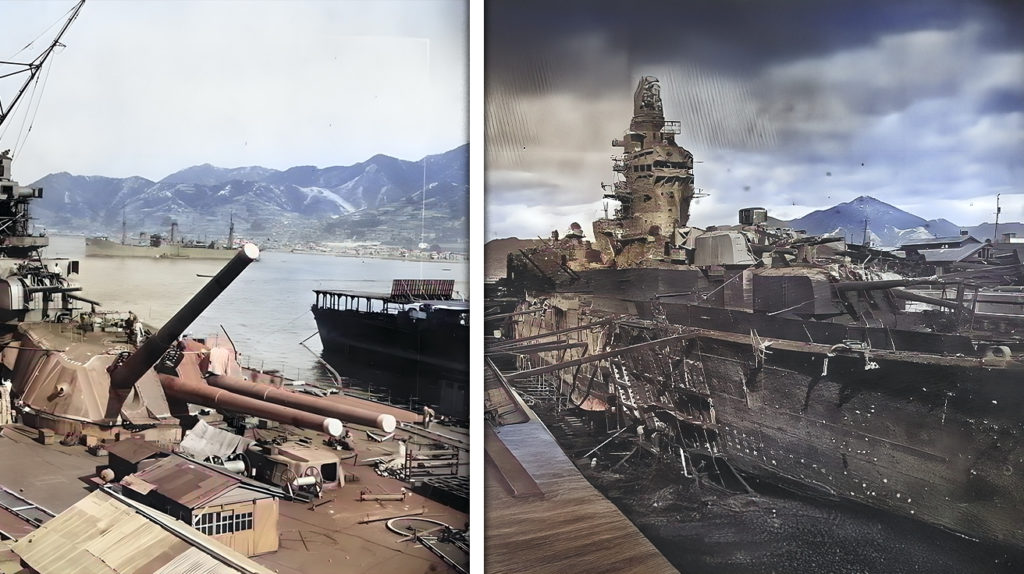

Shrouded in secrecy that would make the CIA blush, Yamato’s 1937 construction process resembled something from a Cold War thriller—complete with screened-off dry docks, coded communications, and workers sworn to silence about those mammoth 46cm guns. The $1.5 billion price tag (in today’s currency) represented resources that could have built Japan’s entire carrier fleet twice over. That’s the problem with military procurement bloat—admirals always fight the previous war. While civilian aviation leapt forward, Japan’s naval establishment doubled down on steel and firepower, making Yamato the maritime equivalent of developing the world’s most advanced typewriter just as computers hit the market. The same institutional blindness affects military planning today, where trillion-dollar fighter programs proceed despite changing battlefield realities. Yamato’s designers created the perfect weapon for a war that would never come.

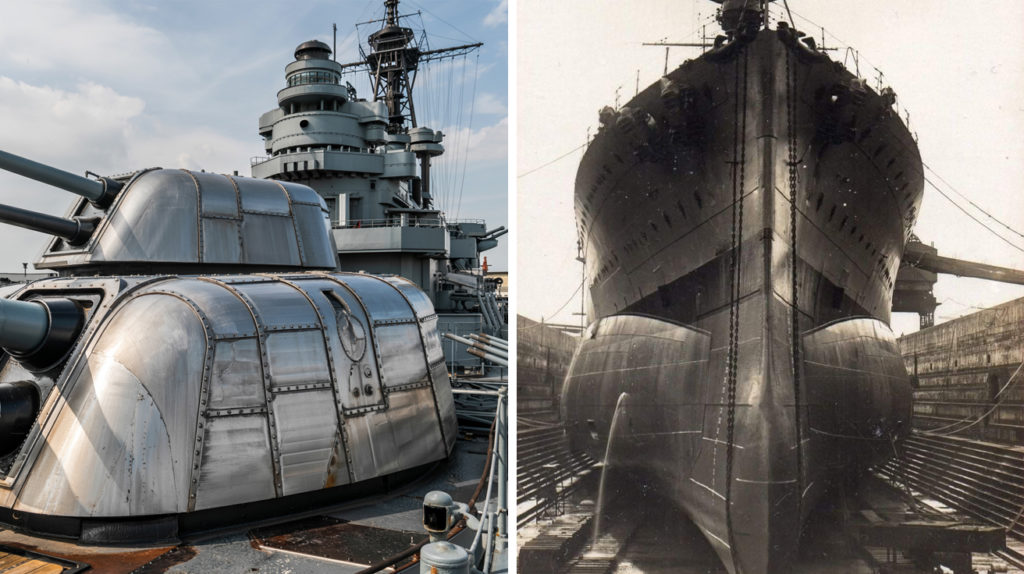

Armament of the Yamato: The Type 94 Guns

Mistaking “biggest” for “best,” military engineers created the Type 94 guns mounted on Yamato—evolutionary dead ends similar to those eight-foot prehistoric birds that couldn’t fly. At 46cm (18.1 inches) in diameter, these guns hurled 1,460kg shells over 42,000 meters, creating blast pressure so intense that sailors needed a football field’s distance during firing. What’s remarkable isn’t just their size but that they relied on manual range-finding in an era when American vessels were already implementing radar guidance. This technological gap mirrors today’s defense departments that still purchase outdated equipment while adversaries deploy next-generation systems. The guns dominated ship design so completely that everything else became secondary, creating a weapon that excelled at a type of naval warfare that would never again occur—comparable to building the ultimate SMS texting phone right as smartphones appeared.

Anti-Aircraft Defenses

Dangerous institutional inertia that plagues military planning reveals itself perfectly in Yamato’s anti-aircraft systems. Engineers equipped the ship with 50 Type 96 triple-barrel 25mm guns, Type 89 .40-caliber guns, and Type 93 ‘Shiki’ 13mm machine guns—impressive on paper but practically medieval in execution. They relied on optical targeting when American ships already deployed radar guidance, akin to bringing binoculars to a drone fight. This technological lag wasn’t accidental but systemic, stemming from Japan’s rigid naval hierarchy that rejected intelligence about American advances. The same phenomenon appears today when established military contractors continue selling outdated systems while pocketing billions in development fees. Yamato’s fatal weakness wasn’t lack of firepower but institutional resistance to disruptive technology—a pattern that continues costing lives in conflicts worldwide.

Yamato’s Weaknesses

Design flaws etched into Yamato’s hull reveal how military procurement often prioritizes tradition over effectiveness. Naval historians point to fundamental errors that doomed the ship—riveted construction instead of welding, rigid torpedo bulkheads instead of fluid-filled chambers, and anti-aircraft systems designed for World War I threats. These weren’t mere engineering missteps but symptoms of institutional calcification—similar to how today’s military-industrial complex continues developing vulnerable platforms that cost billions while being defeated by much cheaper systems. The admirals who approved Yamato’s design weren’t stupid; they were trapped in organizational thinking that rendered them incapable of acknowledging warfare’s changing nature. The same cognitive bias drives modern defense spending, where contractors deliver gold-plated vulnerability while calling it unmatched capability.

Final Mission: Okinawa

Tragic endpoint of institutional delusion manifested itself on April 6, 1945, when Yamato embarked on its suicide mission to Okinawa. Sending the battleship on a one-way mission to beach itself as a stationary gun platform wasn’t merely desperate—it was the military equivalent of burning money to generate heat. The mission lacked air cover in an era dominated by carrier warfare, comparable to deploying tanks without infantry support in urban environments today. By 10 AM, deteriorating weather created a cloud cover that American aircraft—guided by radar systems Japan had dismissed as unnecessary—used to mask their approach. This mission represents what happens when military leadership runs out of ideas but can’t admit strategic defeat—a pattern repeating across conflicts from Vietnam to Afghanistan.